Eternal Light in Glass: The Tiffany Windows of Rosehill Mausoleum

Explore how these stained glass masterpieces transform this massive mausoleum’s interior into a luminous, sacred, and historic space.

It’s no exaggeration that the Rosehill Cemetery Community Mausoleum is one of Chicago’s most underrated and truly hidden gems. From the outside, this behemoth of a building has visual impact on par with the Field Museum or Art Institute, and houses almost as much history and artwork. It is not only a fantastic place to tangibly connect with history, but also to marvel at world-class art and design.

Besides the stonework, bronze work, glasswork, and mosaic-work which may be found in abundance within the mausoleum’s hallowed halls, the building itself is an example of Chicago excellence in architecture.

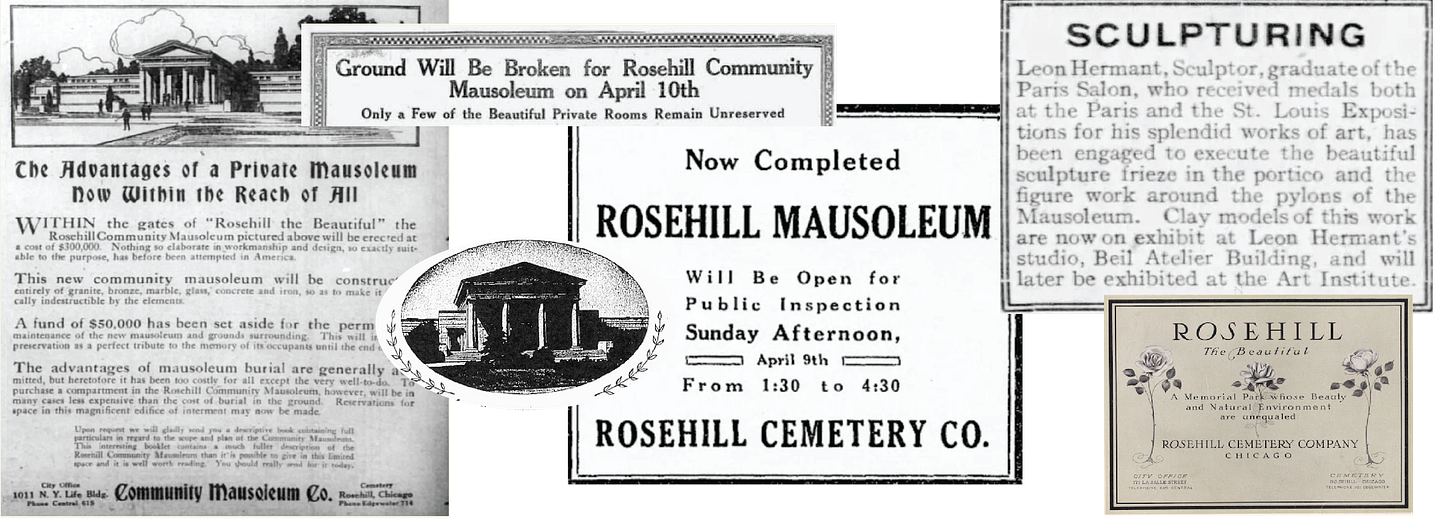

Rosehill Cemetery was chartered Feb. 11, 1859, and remains the largest cemetery in the city of Chicago (1). The Rosehill Community Mausoleum, dedicated in 1914 and designed by Sidney Lovell (who himself is entombed within), is Chicago’s largest (2) and perhaps the most architecturally significant community mausoleums. Built within the grounds of the cemetery, the mausoleum was an ambitious undertaking that expanded multiple times over the decades to accommodate increases in the demand for above-ground entombment, a practice that was once reserved for the wealthy but became more accessible to all Chicagoans through this shared structure.

Entombment options in the mausoleum includes single-occupancy, full-casket crypts as well as ‘family rooms’, which are small rooms with up to eight individual crypts.

Constructed primarily from granite, Italian Carrara marble, bronze, and reinforced concrete, the mausoleum was designed for permanence and prestige. The classical Greek Revival main entrance lends grandeur to the structure, however there is a side entrance to access the mausoleum on the building’s south side since the main entrance is always locked.

From its inception, Rosehill Mausoleum was marketed as a modern, sanitary alternative to traditional burial, offering climate control, ventilation, and perpetual care funded through multiple trust funds. As it grew, it attracted some of Chicago’s most prominent figures, including retail titans Aaron Montgomery Ward and Richard Warren Sears, philanthropist John G. Shedd, and Governor Richard B. Ogilvie. Advertisements at the time emphasized the exclusivity of private rooms, many of which were customized with sculpted bronze doors and personalized stained glass.

Expansions continued over the decades, with new sections added to increase capacity and meet rising demand. Promotional materials highlighted its unmatched craftsmanship, with sculptural work by Leon Hermant and Lorado Taft, and an emphasis on its indestructibility, comfort, and dignity. The mausoleum was positioned as a prestigious resting place, often compared to Westminster Abbey in grandeur.

Many of the private family rooms feature stained glass windows, including works by Louis Comfort Tiffany, son of the founder of Tiffany & Co. Charles Lewis Tiffany (1812-1902), making this mausoleum home to one of the largest non-ecclesiastical collections of Tiffany windows in the world.

Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Tiffany Studios was one of the most innovative design firms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, revolutionizing stained glass, decorative arts, and interior design. Established in the 1870s, the studio flourished in the Art Nouveau era, becoming known for its groundbreaking techniques, including opalescent and Favrile glass, which allowed for unprecedented depth, color variation, and luminosity in stained glass. Unlike many traditional workshops, Tiffany’s studio was defined not just by its artistic mastery but by its progressive employment practices and a unique culture of experimentation and discovery, which fueled its most celebrated works.

The heart of Tiffany Studios’ success was Louis Comfort Tiffany’s insistence on pushing artistic boundaries. He encouraged his artisans—whether seasoned professionals or newcomers—to experiment with materials, develop new techniques, and embrace trial and error as part of the creative process. This philosophy led to the refinement of methods like plating (layering multiple pieces of glass for added depth), drapery glass (used to mimic the folds of fabric), and confetti glass (scattered flecks of color to add visual texture). These innovations transformed stained glass from a rigid craft into a dynamic, painterly medium.

Tiffany understood that true artistry often came through (often accidental) discovery, and created a studio environment where his workers—especially his female artisans and immigrant craftsmen—had the freedom to test new ideas. Instead of rigidly adhering to templates, Tiffany’s designers and glass selectors were encouraged to make creative choices, allowing each window and lamp to be unique, even within standardized designs. This room for experimentation meant that many of Tiffany’s best works were organic, evolving compositions, often subtly different from initial sketches due to in-studio discoveries.

Perhaps nowhere was Tiffany’s experimental philosophy more evident than in his Women’s Glass Cutting Department, sometimes referred to as ‘The Tiffany Girls’. Led by artists such as Agnes Northrop and Clara Driscoll, this all-female team was responsible for selecting, cutting, and assembling glass for some of Tiffany’s most intricate and iconic glass-based designs, including the Dragonfly and Peony lamps and many of the landscape and floral windows such as those found in Rosehill Mausoleum.

Unlike other studios where women were relegated to menial or repetitive work, Tiffany gave the Tiffany Girls creative autonomy, allowing them to explore new ways of layering, shading, and cutting glass to enhance color transitions and natural effects. Driscoll, in particular, was encouraged to develop new glass selection techniques that resulted in some of the most sophisticated color gradations ever achieved in stained glass.

Tiffany’s belief in experimentation over rigid perfection gave his female artisans a rare opportunity for artistic expression, allowing them to produce windows and lamps that felt alive with movement, depth, and emotion. This approach was revolutionary in an era when women were often excluded from serious artistic innovation.

Tiffany Studios was also notable for its employment of immigrant artisans, particularly from Italy, Ireland, Germany, and Eastern Europe, who brought centuries-old glassmaking, metalworking, and mosaic techniques to the workshop. These artisans were not just workers—they were integral collaborators, encouraged to refine old-world techniques through modern experimentation.

Unlike other employers of the era who sought to minimize risk and maximize efficiency, Tiffany embraced the creative potential of trial and error, often tasking immigrant artisans with testing new combinations of glass plating, acid etching, and color mixing to achieve the studio’s signature luminous effects. This culture of open-ended discovery helped perfect Favrile glass, a method in which color was infused directly into the glass rather than painted on the surface, allowing for rich internal luminosity that changed with the light.

Tiffany’s progressive mindset extended beyond artistic experimentation—he also broke labor norms of the time, offering women and immigrant workers higher wages and greater opportunities than many other studios. His policy of equal pay for skilled labor, regardless of gender, was unheard of in the decorative arts industry at the time.

Tiffany’s studio valued talent over traditional social hierarchies, rewarding those who contributed to innovation rather than those who merely conformed to expectations. This belief in the power of the individual artisan contributed to Tiffany Studios’ reputation for producing some of the most unique, richly detailed stained glass windows in the world—including those housed in Rosehill Mausoleum, where plating, color blending, and sculptural drapery glass create a sense of depth and movement rarely seen in funerary art.

Though Tiffany Studios closed in 1932 due to financial difficulties during the Great Depression, its spirit of artistic experimentation, inclusivity, and boundary-pushing craftsmanship left a lasting legacy. The studio’s revolutionary glass techniques continue to shape modern stained glass art, and the contributions of Clara Driscoll, the Tiffany Girls, and immigrant artisans have since been recognized as integral to Tiffany’s success.

While many of Tiffany Studios’ most famous works adorn churches and cathedrals, where stained glass traditionally served a liturgical function, the windows at Rosehill reflect a different application of Tiffany’s artistry—one deeply rooted in the evolution of funerary aesthetics in the early 20th century.

Louis Comfort Tiffany’s presence at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago was a turning point for his studio’s reputation and commercial success, particularly in the Midwest. The Chicago World’s Fair was one of the largest and most influential exhibitions of the 19th century, showcasing cutting-edge innovation, architecture, and design to over 27 million visitors. Tiffany Studios used this opportunity to captivate the public and establish itself as a premier name in decorative arts, leading to a surge in commissions for private residences, churches, and mausoleums in Chicago.

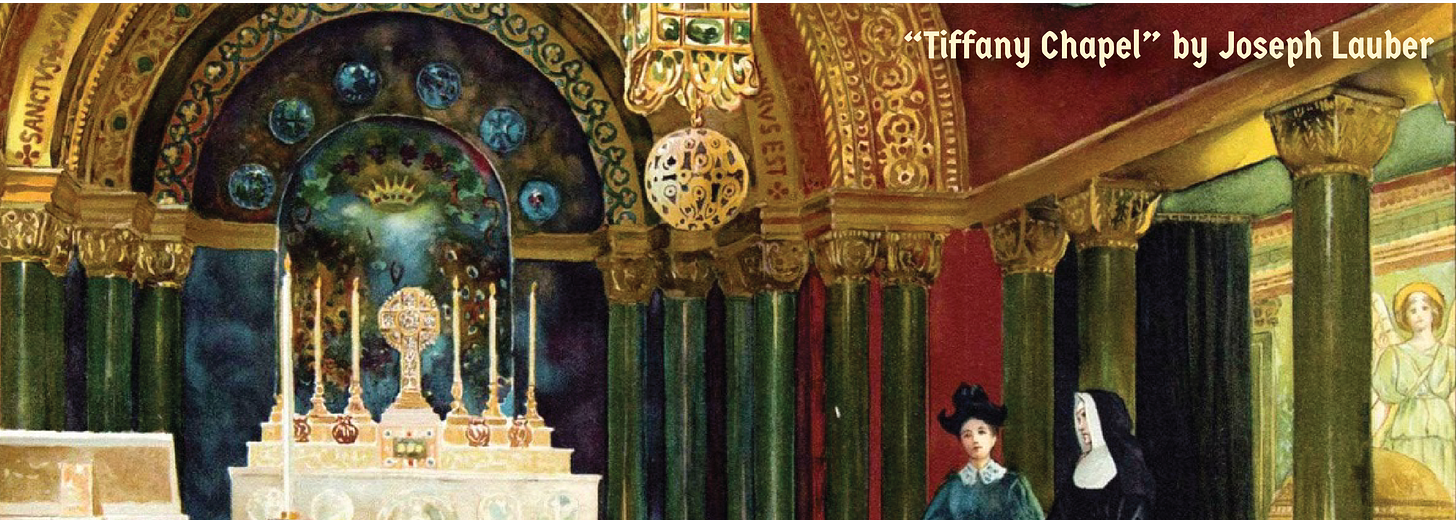

Tiffany’s mastery of light, texture, and opalescent glass techniques. The chapel’s success reinforced Tiffany’s reputation as an innovator in ecclesiastical design, and its mesmerizing use of glass plating, iridescent hues, and multi-layered color effects introduced visitors to an entirely new way of thinking about stained glass—not just as decoration, but as a transformative art form.

After changing hands several times over the decades and relocations between Chicago and New York, in 1996 the Board of Trustees of the Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation endorsed an expansion project for the Morse Museum that would reassemble Tiffany’s 1893 chapel. A team of architecture, art, and conservation experts was named to begin the more than two-year project of reassembling the chapel. The chapel opened to the public in April 1999, the first time since it was open at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago (4)

The massive attendance at the Chicago World’s Fair meant that Tiffany’s work reached a national audience, but it had a particularly profound impact on Chicago’s elite, who sought to incorporate Tiffany’s designs into their homes, businesses, churches, and memorials.

His glasswork became a status symbol, signifying both artistic taste and wealth. The city, already in the midst of rapid architectural transformation after the Great Fire of 1871, eagerly embraced Tiffany’s vision of glass as an essential element of modern design, aided in the claims of Tiffany glass mosaics being ‘fireproof’.

The Chicago Cultural Center, just blocks away, is home to one of the most stunning stained glass domes in the world: the Tiffany Dome in Preston Bradley Hall. Installed in 1897, is the largest Tiffany glass dome in existence, spanning 38 feet in diameter and made of over 30,000 pieces of Favrile glass arranged in an intricate fish-scale pattern (5). Designed to filter natural light through its iridescent opalescent glass, the dome creates a constantly shifting glow of blues, greens, and ambers. Encircled by a Latin inscription on learning and wisdom, it originally crowned the Chicago Public Library’s circulation room. After decades under a protective skylight, a 2008 restoration removed the covering, restoring Tiffany’s intended effect of soft, diffused natural light illuminating the glass from above.

The opening of the new Marshall Field's State Street store in 1902 introduced a public landmark and spectacle, and the highlight of the store’s design was a Tiffany mosaic dome, completed in 1907 and supposedly commissioned by John G. Shedd, who was so impressed by Tiffany’s work that he hired Tiffany Studios to design his own family room’s stained glass window in the Rosehill Mausoleum- today one of the most iconic and well-visited rooms in the structure. The Marshall Field glass mosaic dome covers six thousand square feet, and is raised six floors above the store’s ground level (6).

It was designed by J. A. Holzer, the chief mosaicist of the studio at the time, and is reputed to be the largest Tiffany dome in existence (7).

Rosehill Mausoleum’s extensive collection of Tiffany stained glass windows is also a direct result of this post-World’s Fair demand.

During this period, mausoleum burial was gaining popularity among the elite as a dignified, sanitary alternative to traditional in-ground interment. The grandeur of a mausoleum, particularly one designed with neoclassical influences like Rosehill’s, allowed families to showcase wealth, status, and taste. Tiffany Studios, known for their innovations in glasswork, became a preferred choice for mausoleum commissions among the well-off, offering personalized, ethereal compositions that transformed cold marble chambers into luminous spaces of reflection and beauty.

The scale of Rosehill’s collection resulted in the Tiffany windows becoming an integral part of the mausoleum’s design. With around 30 confirmed Tiffany windows spread throughout the building, their presence underscores how Tiffany’s funerary commissions were not just religious but also secular—designed to comfort mourners, reinforce themes of eternity and transcendence, and align with the Gilded Age preference for personalized, artistic, and symbolic memorialization.

Tiffany’s Favrile glass techniques, opalescent layering, and intricate use of drapery and confetti glass gave depth and movement to the landscapes, allegorical figures, and floral compositions found in the Rosehill windows. Many depict flowing water leading to distant mountains, a motif symbolizing the passage of the soul, while others feature irises, lilies, and allegorical figures, reinforcing themes of resurrection and eternal peace.

In comparison to church settings, where Tiffany’s stained glass often served to illustrate biblical narratives, Rosehill’s windows take on a more personal, introspective role. Here, the interplay of light, color, and nature creates an atmosphere of serene contemplation, not tied to any single religious tradition but speaking to broader ideas of memory, transition, and the eternal.

The presence of triptych Tiffany windows in larger private family rooms, such as those for John G. Shedd and Walter P. Murphy, further highlights the exclusivity and prestige of these commissions. The highly detailed compositions and careful use of color and texture distinguish them from standard mausoleum glasswork, making Rosehill a rare example of how stained glass artistry was integrated into secular memorial architecture on a grand scale.

Additionally, mosaics which have yet to be confirmed as Tiffanies in the rooms of Narcisa Niblack Thorne (creator of the Art Institute’s Thorne Miniature Rooms) and Richard Warren Sears (founder of yes, that Sears) add even more layers to the artistic history and impact of the mausoleum.

This precious and enviable collection cements Rosehill Mausoleum’s role as not just a burial place but an artistic landmark, preserving some of Tiffany Studios’ finest work in a setting dedicated to remembrance rather than worship. As one of the largest surviving collections of Tiffany’s secular stained glass, it remains an important site for both art history and Chicago’s cultural heritage, showcasing how light and glass continue to shape the way we memorialize the dead. Tiffany’s mastery in glass ensures that, even in death, there is beauty, color, and the quiet glow of eternity.

Sources

“Olsen, Morgan, and Emma Krupp. "The Most Hauntingly Beautiful Cemeteries in Chicago." Time Out Chicago, 29 Sept. 2023. https://www.timeout.com/chicago/things-to-do/beautiful-cemeteries-in-chicago

“Rosehill Cemetery: Chicago’s Largest, Most Diverse”, Alice Adams and Jim Kurtz, American Cemetery & Cremation. https://www.acm-digital.com/acm/may_2020/MobilePagedArticle.action?articleId=1582230#articleId1582230

Tiffany & Co. "Louis Comfort Tiffany." Tiffany & Co. Press Room. https://press.tiffany.com/spokespeople/louis-comfort-tiffany/

The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art. "The Tiffany Chapel." Morse Museum. https://morsemuseum.org/louis-comfort-tiffany/tiffany-chapel/

"Preston Bradley Hall Tiffany Dome." Chicago Cultural Center, City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events. https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/depts/dca/supp_info/chicago_culturalcenter-tiffanydome.html

"Department Stores." Encyclopedia of Chicago, Chicago Historical Society, 2005. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/373.html

"Marshall Field & Company Store (Now Macy's on State Street), 101–149 North State Street, Chicago: The Tiffany Favrile Glass Mosaic Domed Ceiling on the Fifth Floor." RIBApix, Royal Institute of British Architects. https://www.ribapix.com/marshall-field-company-store-now-macys-on-state-street-101-149-north-state-street-chicago-the-tiffany-favrile-glass-mosaic-domed-ceiling-on-the-fifth-floor_riba45630

"Tiffany Video from Driehaus Museum." World’s Columbian Exposition: Chicago 1893, 12 Apr. 2020, www.worldsfairchicago1893.com/2020/04/12/tiffany-video-from-driehaus-museum/.

"Neustadt Gallery." The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass, www.theneustadt.org/exhibitions/neustadt-gallery

Rosehill has over 40 Tiffany Studios’ memorial windows-not 30.

The two glass mosaics are Tiffany Studios’ designs.